PIV (particle image velocimetry) appeared more than three decades ago, and it became widely used as a quantitative flow measurement solution ( Adrian, 1991 2. Large snow particles ( D max ≫ 100 μm) exhibit tangled falling trajectories due to the combined effects of irregular particle shape, size, and flow regime (i.e., Reynolds number).Ī large variety of experimental techniques are nowadays available to investigate complex flows. Hence, the interaction with the surrounding air becomes non-linear (large D max implies large Re) ( Abraham, 1970 1.įunctional dependence of drag coefficient of a sphere on Reynolds number,” Phys. The fall speeds of sub-100 microns ice crystals,” Q. ), and for snowflakes larger than few micrometers, Stokesian dynamics is not valid anymore ( Brady and Bossis, 1988 6. Snow crystals display different sizes and shapes in nature ( Kikuchi et al., 2013 24.Ī global classification of snow crystals, ice crystals, and solid precipitation based on observations from middle latitudes to polar regions,” Atmos. The shape and the orientation of falling ice particles influence snow precipitation and are crucial for weather prediction and polarimetric radar measurements, respectively. Applying a co-moving frame to the experimental data to account for the particle movement or filtering the numerical data on larger grids reduces these differences only to some extent, implying that an unsteady fall significantly alters the average wake structure as compared to a fixed particle model.

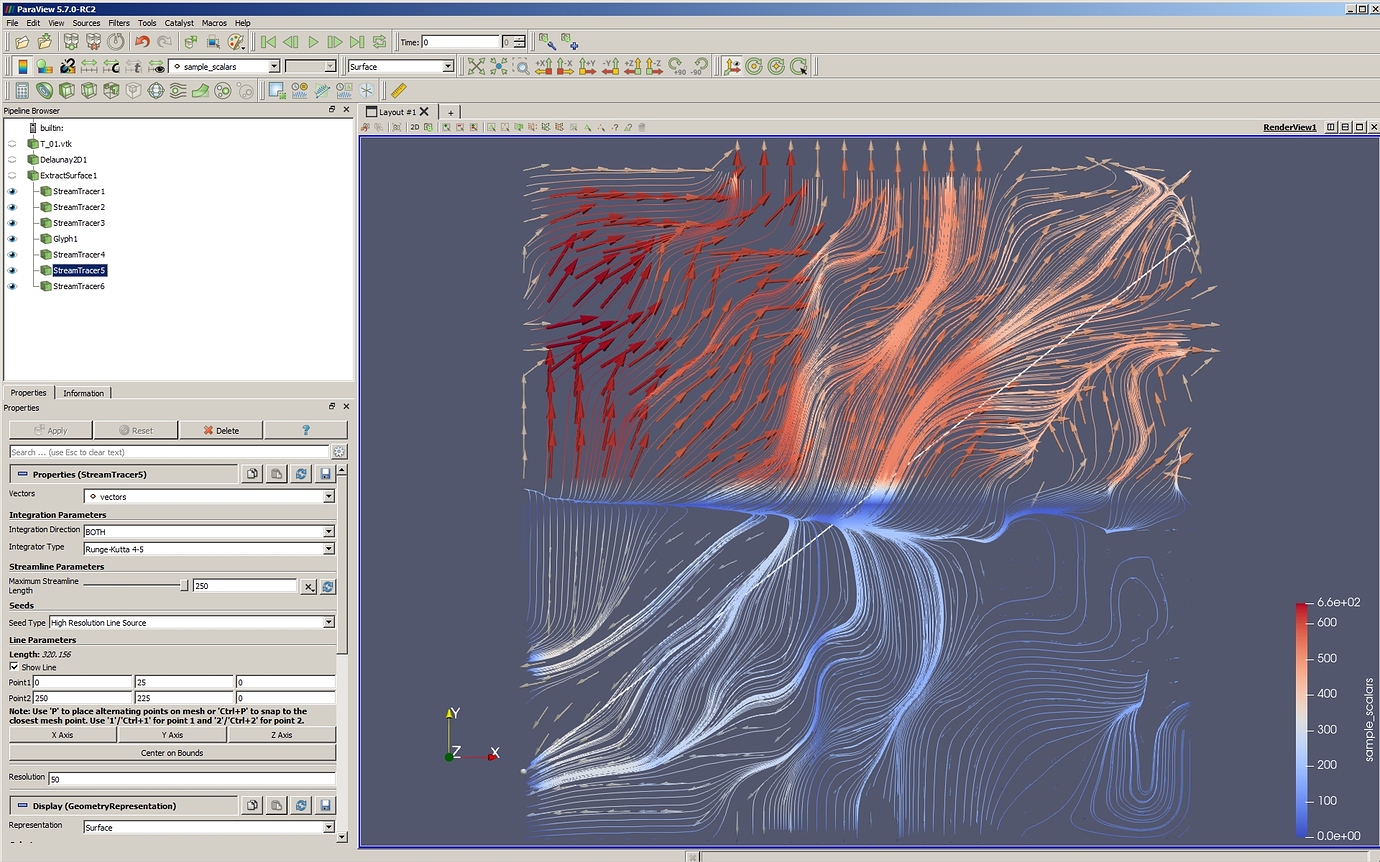

At moderate/high Re (unsteady falling motion), larger differences are present. For steadily falling snowflakes, the fixed-particle model can properly represent the wake flow with errors within the experimental uncertainty (☑5%). First, we cross validate the two approaches for low Re cases, where close agreement of the wake features is expected, and second, we assess how strongly the unsteady falling motion perturbs the average wake pattern as compared to a fixed particle at higher Re. In this work, we compare both approaches on time- and space-averaged flow quantities in the snowflake wake. Delayed-detached eddy simulations of fixed snow particles do not realistically represent all the physics of a falling ice particle, especially for cases with unsteady falling attitudes, but accurately predict the drag coefficient and capture the wake characteristics for steadily falling snowflakes. Time-resolved, three-dimensional particle tracking velocimetry (4D-PTV) experiments of free-falling, three-dimensional (3D)-printed snowflakes' analogs shed light on the elaborate falling dynamics of irregular snow particles but present a lower resolution (tracer seeding density) and a limited field of view (domain size) to fully capture the wake flow. Experimental and numerical approaches have their own advantages and limitations, in particular, when dealing with complex phenomena such as snow particles falling at moderate Reynolds numbers ( Re).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)